We promise these to be last passages we ever quote from Cornelia Dean's Against the Tides.

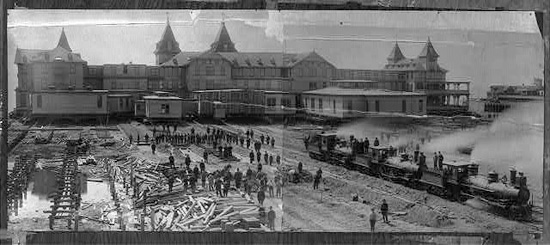

In April 1888 [...] Brighton Beach Hotel on Coney Island, a multistory frame structure with scores of rooms, was moved 450 feet inland when it was threatened by erosion. Its owner, the Brooklyn, Flatbush and Coney Island Railroad, jacked the thing up and hauled it inland in one piece, using six locomotives, 112 flatcars, and twenty-four specially laid tracks. The structure moved “at a fast walk,” Scientific American reported in its issue of April 14, 1888, adding: “No difficulty of any kind was encountered.”

Images from that issue of Scientific American, including one from the Library of Congress, are replicated below:

A century and a decade later, another substantial structure on the Atlantic coast was moved wholly intact: the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse.

When it was built in 1870, the lighthouse was located 1600 feet inland. Sited on one of the most unstable landscapes, where you can witness geological changes occurring in real time, it saw the shoreline getting closer and closer over the years. People feared that without protection the waves would eat away at its foundation, toppling it over. And protect it they tried.

First, the U.S. Navy “installed three groins to trap sand in front of it. Erosion worsened downdrift at the lighthouse. The downdrift groin was strengthened, which helped somewhat, but waves soon began cutting around its southern flank, threatening the lighthouse again.”

Then a businessman helped with the purchase of “the latest thing in shoreline protection technology: artificial seaweed.” After it was installed, “the project quickly failed. Fronds broke loose and caught in the propellers of passing boats. Others ended up in tangles on the beach. It was a mess.”

Asked by officials from the National Park Services, the Army Corps of Engineers drew up plans for a seawall to surround the Cape Hatteras beacon. Everything outside this defensive wall would be allowed to erode away, essentially turning the lighthouse area into a fortified island. As the coastline moves further inland, this new artificial island would migrate out to sea. Should the coastline itself retreat and march out back to sea, perhaps in the next Ice Age, both lighthouse and island would rejoin the mainland: an image we certainly like imagining. Problem was the seawall would block much of the lighthouse, especially its photogenic base. Moreover, the structure rests on a foundation of yellow pine logs. Their “strength is legendary” but could only be maintained if submerged in fresh water. If the lighthouse goes out to sea, salt water will flush it out, and if the fresh water goes, so goes the foundation and the lighthouse.

Since no one wanted to just let nature take its course on the coast and let the lighthouse collapse into a Picturesque ruin for Neo-Romantic tourists, the only other “sensible approach to accelerating erosion,” as the enfant terrible of coastal geopolitics, Orrin H. Pilkey, and others advocate, is: managed retreat.

In July, 1999, “the lighthouse, traveling on steel plate resting on iron rails, arrived at its new site, 1,600 feet inland from the sea.”

Architecture here has been yanked from its isolation and thrown into the wilds of ambiguous conditions, to dynamic forces and flows. If only for a short time, it was opened to the landscape.

The Retreating Village

Coastal Retreat

Other Bathing Machines

This House Turns and Returns, Too

Moving the Vatican Obelisk

The Supersurface of Architectural Diaspora