The latest peripheral from Subtopia points us to this recent article in The New York Times about atomic tourism in the American Southwest.

At the Titan Missile Museum, we learn, visitors can “stare up at a 103-foot-tall intercontinental ballistic missile from the bottom of a hardened silo buried in the Arizona desert;” see how the crew rested (or experienced countless anxiety attacks) in spartan conditions; feel the thick, cold steel of the blast doors; and even jiggle around with the switches on the firing console.

Meanwhile, at the Nevada Test Site, you get to see the actual effects of Armageddon.

“As the bus headed toward the site of a 37-kiloton blast in 1957,” writes Henry Fountain, “it drove past the mangled remains of several shelters made of aluminum. Nearby was a blasted bank vault, an experiment to see whether money and valuable documents could survive nuclear war. There were twisted I-beams from a section of a trestle bridge, large poles for testing window glass and concrete bunkers that looked relatively unscathed.”

And there are also “the remains of the Apple 2 project, a 1955 explosion designed to test civil defenses. Parts of a small town were constructed for the test, with stores, cars and houses complete with refrigerators filled with food and mannequins dressed in clothing.”

Surprisingly, the

For some reason, we are reminded of a design competition, held many years ago, for a permanent warning sign for Yucca Mountain, the nation's first long-term geologic repository for spent nuclear fuel and high-level radioactive waste.

The winning design, by Ashok Sukumaran, features “genetically engineered Yucca catcus which turns various shades of blue depending on the levels of radiation in the area.”

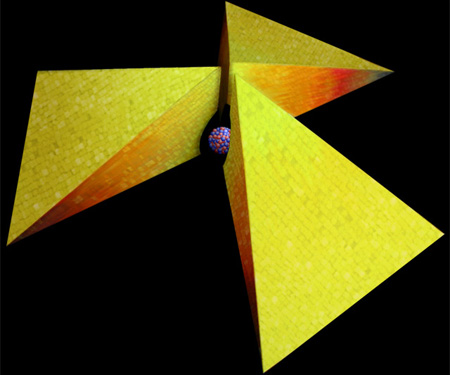

This is a giant 3-D version of the iconic radioactive danger sign designed by Yulia Hanansen: “We stylized the conventional sign, arriving at the conjoined triangle design shown below. The sign has sharp edges, representing an acuteness and seriousness appropriate for the warning it must convey. It is a pyramidal structure which can be perceived as a message containing another message. The monument itself becomes a symbolic mountain where one will be able to enter it and learn about what lies within.”

Scott A. Ogburn and Linda Buzby designed these nuclear waste mausoleums.

None of which, of course, will ever prevent anyone from visiting the site — even if our descendants still understood English, and the universal radioactive danger sign remains iconographically legible 10,000 years from now. Build a field of menacing concrete spikes, and it becomes a popular destination. CLUI will send busloads of tourists.

What should be done in the intervening thousands of year is to develop an anti-radiation pill or the fast-acting anti-tumor pill, so that with these miraculous medical breakthroughs, future travelers will go on so-called radiation tours.

As you walk through the excavated labyrinth of Yucca Mountain during these tours, you become listless, nauseous. Going deeper and deeper into the caverns — damp, mildewed surfaces; stale air; pyramids of light falling heavily on your weakening body — you begin to have what will become the worst migraine of your life.

Then your hair falls off.

Others in your group had taken a different path and are now suffering from beta burns. Still others, on a different scenic route, are vomiting every few steps, their nose bleeding.

But obviously, all is well; you've taken the pills. Radiation poisoning is as safe as a Disney ride or a stroll through the park.

And as a souvenir you'll be given a wig at the gift shop.

The Bureau of Atomic Tourism

Cold War National Park

Dugway Proving Ground National Park