The Broken Column House is so named because it takes the form of a ruined classical column: truncated, jagged and riven with fissures. It was built by the aristocrat François Nicolas Henri Racine de Monville who used it as his main residence during the years immediately before the French Revolution. Nestled within the confines of Monville's private pleasure garden, called the Désert de Retz, it “stands like a solitary beacon, signaling the visitor to prepare for an encounter with the bizarre.”

And what bizarre encounters!

Visitors to the Désert would have encountered not just the Broken Column but also the Chinese House and the Tartar tent, which was made not out of fabric but tin metal, “gay with painted stripes” and erected on an artificial island in an artificial lake. Like many large gardens, it had a grotto, through which one would have entered the property (in other words, before Paradise, one must first journey down to the Abyss). There was also a peasant-chic thatched-roof cottage and the false ruins of a Gothic church. You could say, then, that the Désert was an outdoor museum of crypto-architectural history. Indeed, Diana Ketcham, in her slim but copiously illustrated book, describes it as “one of the glories of the architecture of fantasy.”

The garden itself was rather eccentric. Set within a natural-looking park were a model farm, a working dairy and an orangerie. Since Monville had no need to earn income from agriculture, these were more for leisure than production. Indeed, one shouldn't be surprised if one learns that some of Monville's guests, many of whom were members of the aristocracy, may have role-played as farmers or milkmaids for an afternoon.

Perhaps stranger things may have happened inside the walls of a garden presided over by a monied gentleman, an inveterate socialite who was said to have been “built like a model,” had “superb legs,” and bedded a different woman every night, either in the house or in any one of his fantastical follies.

One might think that Monville was psychologically unstable, the Ludwig of the Ancien Régime, and that his gardens were but the whims of one with too much money on his hands. But the Désert was a robust testing grounds for new forms and theories of landscape and architecture. Perhaps not unlike the Nevada Test Site and other military training facilities, it was an experimental terrain within which alternative systems to, say, Le Nôtre and Vitruvius, were dreamt up, cultivated and then promoted.

To a more modern visitor, meanwhile, fed with a steady diet of science fiction movies and literature, the Broken Column may evoke a distant Age of Titans, when giants roamed the land and built massive temples and homes, and the epic conflagration that ushered in the era's end, and then in the post-apocalyptic wasteland, the Lilliputian survivors made shelters out of the ruins and waited for Nature to return and erase the evidence of the disaster.

As absurd as that may sound, it is the sort of reaction Monville and other contemporary designers and patrons of irregular gardens in the English style intended to elicit. With their carefully composed views, such gardens were meant as the “stage sets for the enactment of fantasies of a pastoral or mythic character” — or “the stage for terror.”

Ketcham elaborates: “The sight of the [column] fragment generates a [...] superhuman dimension in the mind of the viewer. A corollary response is the realization that giants are at hand. Coming upon the Column, a human visitor feels the fear of the fairy tale hero stumbling up against the giant's boot.”

For the viewer who identifies with the giants, on the other hand, or with the old Testament God who struck down the Tower of Babel, the conceit of the colosal temple is exhilarating. In our unbelieving age, it is easier to respond to the purely spatial implications of the imaginary real. According to the Doric formula, height equals eight times the diameter, the full-scale column would stand at 384 feet. The architectural footprint of such a temple would extend beyond the borders of the garden.

Scale, then, becomes a technique with which Monville could create “a mood of altered reality.”

Ketcham again: “In the conventional picturesque garden, the presence of follies enhances the viewers' sense of physical and intellectual power, placing them in a controlling relation to the architecture of all times and all places, which has been scaled down to the comfortable proportions of the rural everyday landscape.” But here at the Désert, “it is the viewer who is reduced, rendered small and bewildered before the mysterious bulk of the Broken Column.”

Comparable contemporary architecture — the ones that you might expect to see in Las Vegas and RoadsideAmerica.com — may be ridden with gaudily clad tourists unknowingly suffering from post-modernist angst or architecture students, with copies of Baudrillard stuffed in their backpacks and gallons of ennui, seeking self-consciously ironic experiences.

The Désert, on the other hand, welcomed guests of a different sort. For instance, Thomas Jefferson, while serving as a minister to France, paid a visit to the Désert and “used elements of the floor plan of the the Broken Column in his design for the University of Virginia rotunda. Other illustrious persons who made it a favored retreat included Madame du Barry, the mistress of Louis XV; the Duc d'Orléans; and Queen Marie Antoinette, who found inspiration there for her English gardens at Versailles.

There are so many interesting things to be said about the Broken Column House and the Désert de Retz, but we'll limit them to two here.

Firstly, the Désert is the only folly garden of France's eighteenth century that still exists close to its original state. Some of the grandest were leveled after the Revolution while others now exist heavily renovated or in fragments, leaving little sense of the original schemes.

But “decades of neglect saved the Désert de Retz from this common fate. Forgotten or ignored by a series of absentee owners, the park and its architectural contents were permitted to decay undisturbed and were taken up only in the 1980s as the object of restoration.”

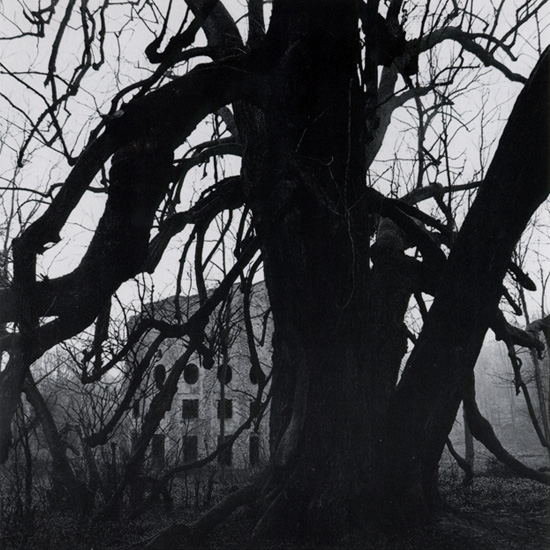

The result is that what the eighteenth century devised as an artificial ruin became in the twentieth century a literal one, an irony whose poignancy has moved all of those who have pushed through the underbrush to enter into this forgotten place.

Secondly, as mentioned above, a program of restoration was carried out in the 1980s and one that still continues today. And therein lies some very interesting questions.

How does one return an artificial ruin, which became a true ruin, back to its original artificiality, a condition which aspired to be what it had become?

How does one restore decay from a state of real decay?

Here one imagines the restorers waking up in the middle of the night, screaming and drenched with sweat, unwilling to return to sleep for fear of dreaming recursively the horrors of authenticity. “Is this a fake crack? A real crack? Fake? Real? Fake? Real?"

Such is the terror of the Picturesque garden.

By Diana Ketcham, 1997.

By Michael Kenna, 1990.

The Broken Column on Google Maps

Flickr: Le Désert de Retz

A Pyramid For Serving Glaciers

At the Gates of the Desert